Identity and Social Relationships

of Young Burakumin - Part I

UCHIDA Ryushi (Researcher, BLHRRI)

Since the 1990’s the situation for young people in

This is not to say that all youth have been placed in positions of hardship. The expansion of class inequality (for example Tachibanaki, ed. 2004) and disparity in academic achievement (Kariya and Shimizu, ed. 2004) is progressing, and those people who come from difficult family backgrounds or who find themselves lacking in academic ability or background, those youth with comparatively low social class backgrounds clearly show a higher incidence of unemployment and are more likely to become Freeters (part-time workers) or NEETs (Not in Education, Employment, or Training). Comparatively low education levels and a lack of job security continue to be a large problem in Buraku communities, and with the present tendency for “youth to be socially disadvantaged” (Miyamoto, 2002), it is arguable that the situation of Burakumin youth is becoming desperate.

In addition to the hardship of leading a life such as this, for Burakumin, there is an added challenge of facing the issues incumbent upon minorities: here, of being Burakumin and of discrimination. There is no question that, due to a variety of measures implemented over the past years, discrimination has been

subdued. However, this does not mean that the anxiety spurred on by discrimination has been totally erased. The fact that the negative social evaluation of Buraku inherent in prejudice and discrimination is shared by minority youth can serve as an indication of the large effect such an evaluation has on the identity of Burakumin youth. Understanding what measures and conditions would allow Burakumin youth to develop a positive rather than a negative identity remains an important issue, particularly in the struggle to develop measures to conquer the conditions of so-called “psychological discrimination” (Okuda 1998). Despite this fact, the accumulated research on the identity of Burakumin youth is still sparse, and there are few works that make clear the relevance of a variety of social relationships to this identity. [1]

In light of this situation, this paper takes results from the “Survey of the Self-Perceptions and Lived Reality of Youth and High School Students,” conducted in 2004 with the Youth Group of the Nara Prefecture Branch of the Buraku Liberation League, and analyzes the identity and social relationships of Burakumin youth.

The concept “identity” has a variety of uses, depending on research discipline. To offer a rough classification, we can sort the approaches into two: psychology, represented by Erikson, takes identity to be the “coherence” and “uniformity” of the ego, within the individual; sociology (social psychology) takes identity to be close to “function,” based upon one’s membership in a group (reference group) or social category (Gleason 1983; Togitsu 1998). The above survey relies on the latter usage; that is to say, it highlights the self-concepts, appraisals, and feelings born of membership in the Buraku social group.

The object of the survey are youth and high school students (typically up to 35 years of age) either involved in the Buraku liberation movement or those accessible by the prefecture Burakumin youth group. The survey methods were as follows: I conducted directed interviews with people, when possible with the help of the prefecture youth group, and used a placement method when interviews were not possible. The survey was conducted between October 2004 and January 2005. There were 267 respondents, of which 202 (75.7%) indicated they were Burakumin.[2] 32 (12.0%) said they did not think they were Burakumin, 28 (10.5%) said they did not know, and 5 (1.9%) did not answer. This study takes as its object the 202 respondents who indicated they were Burakumin, and makes its analysis based on them. [3]

1. Self-Awareness of Burakumin

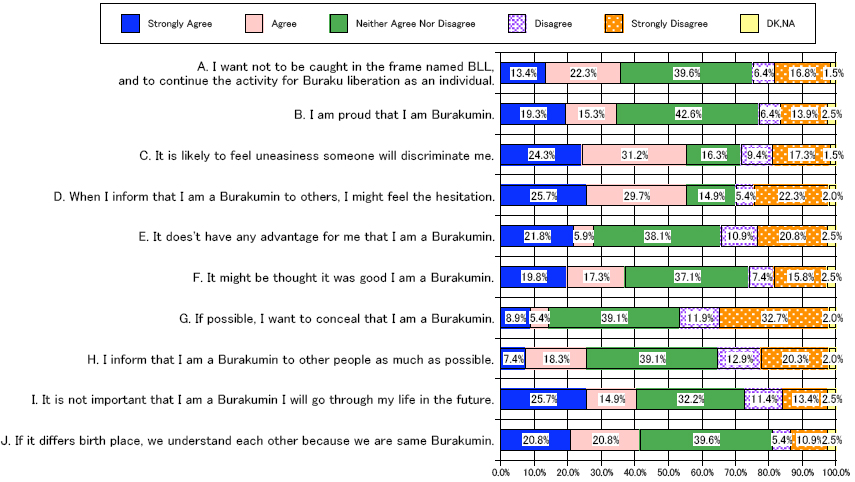

Figure 1 indicates the self-consciousness of being Burakumin of those who indicated they were Burakumin. Responses of “Strongly Agree” or “Agree” were in the majority on the following questions: “Knowing that I could face discrimination because I am Burakumin at times makes me feel uncomfortable” (55.5%) and “I occasionally hesitate when I tell someone else I am Burakumin” (55.4%). More than half of the people experience unease at the thought of discrimination or coming out. Conversely, responses of “Disagree” or “Strongly Disagree” were high for “G If possible, I would like to hide the fact that I am of Buraku origin” (44.6%). All together, while unease might be high, the results indicate that people do not necessarily want to hide their Buraku origin.

Figure 1 – Self-Awareness of Burakumin

2 Identity and Social Relationships of Burakumin

2-1 I conducted a principle component analysis to get a comprehensive understanding of the answers to the ten questions regarding being Burakumin.[4] Table 1 shows the results.

Table 1 – Principle Component Analysis of Self-Consciousness of Being Burakumin

|

Principal 1

|

Principal 2

|

Principal 3

|

|

| A. I do not want to work within the BLL framework but would rather continue activities as an individual. |

0.590

|

0.140

|

0.324

|

| B. I am proud that I am Burakumin. |

0.792

|

-0.122

|

0.254

|

| C. Knowing that I could face discrimination because I am Burakumin at times makes me feel uncomfortable. |

-0.024

|

0.859

|

0.086

|

| D. I occasionally hesitate when I tell someone else I am Burakumin. |

-0.178

|

0.858

|

0.090

|

| E. Being Burakumin does not provide me with any advantages. |

-0.691

|

-0.096

|

0.227

|

| F. I tend to think it is a good thing that I am Burakumin. |

0.825

|

0.029

|

-0.027

|

| G. I hide the fact that I am Burakumin when possible. |

-0.622

|

0.554

|

0.073

|

| H. I tell other people that I am Burakumin as much as possible. |

0.608

|

-0.152

|

0.155

|

| I. Being Burakumin has little impact on how I lead my life. |

-0.306

|

-0.531

|

0.191

|

| J. I have a mutual understanding with other Burakumin, even if our birthplaces are different. |

0.117

|

0.051

|

0.891

|

| Eigenvalue |

3.186

|

2.042

|

1.032

|

| Variance (%) |

31.9

|

20.4

|

10.3

|

|

Positive

Identity |

Discomfort with

Discrimination |

Feelings

of Commonality |

1:Strongly Agree, 2:Agree, 3:Neither Agree nor Disagree, 4:Disagree, 5:Strongly Disagree

The first component is labeled “Positive Identity” and reflects a positive evaluation of being Burakumin because of a high component loading in “F I tend to think it is a good thing that I am Burakumin” or “B I am proud that I am Burakumin.” The second component is labeled “Discomfort with Discrimination,” because of a high component loading in “C Knowing that I could face discrimination because I am Burakumin at times makes me feel uncomfortable” or “D I occasionally hesitate when I tell someone else I am Burakumin.” The third component is labeled “Feelings of Commonality” because of a high loading in “J I feel mutual understanding with other Burakumin, even if our birthplaces are different.”

The above results allow us to summarize a pattern of Burakumin youth identity with “Positive Identity,” “Discomfort with Discrimination,” and “Feelings of Commonality.” Below there is an analysis of the relationship between the two identity parameters, “Positive Identity” and “Discomfort with Discrimination,” and other parameters.

2-2 Relationship to Attributes

There is no noticeable difference in the identity parameters according to sex.

Table 2 shows correlation coefficients for identity parameters and age and education level. “Discomfort with Discrimination” varies widely according to each of these. “Discomfort with Discrimination” rises both with age and level of education.

Table 2. Correlation Coefficient between Age, Education Level, and Identity Variables

|

Positive Identity

|

Discomfort with Discrimination

|

Feelings of Commonality

|

||

| Age (N=196) |

-0.103

|

0.214

|

**

|

-0.049

|

| Education Level (N=195) |

-0.071

|

0.232

|

**

|

-0.097

|

*Graduated junior high school, Attending high school and leaving school before graduation =9.

Graduated high school, Attending junior college, Junior college leaving before graduation, Attending vocational school or various schools, Vocational school or various schools leaving before graduation, Attending university or university leaving before graduation = 12

Graduated junior college or Vocational school or Various school = 14

Graduate school, Attending graduate school, Graduate school leaving before graduation or graduated graduate school = 16

2-3 Relationship to Discrimination Awareness and Experience of Discrimination

Table 3 shows correlation coefficients for identity parameters and perception of the frequency of discrimination in employment, dating, and marriage.

Table 3.Correlation Coefficient between Discrimination Awareness and Identity Variables

|

Positive identity

|

|

Discomfort with discrimination

|

|

Feelings of Commonality

|

|

||

| A | Getting employment (N=196) |

-0.194

|

**

|

-0.407

|

**

|

-0.016

|

|

| B | Love with non-Burakumin (N=197) |

-0.103

|

|

-0.434

|

**

|

-0.171

|

*

|

| C | Marriage with Non-Burakumin (N=197) |

-0.153

|

*

|

-0.446

|

**

|

-0.100

|

|

* The correlation coefficient is significant in 5% level.

*1 = Often, 2 = Sometimes, 3 = Neither Often nor Never, 4=rarely, 5 = never

Awareness of discrimination correlates highly with “Discomfort with Discrimination.” For all three forms of discrimination, the class of people who answered, “Often” tend to show high level of discomfort with the thought of discrimination.

On the other hand, if we look at the correlation with “Positive Identity,” for employment and marriage discrimination, we see that those who think they “often” tend to be those who view their identity positively. A strong awareness of discrimination is tied to a positive evaluation of one’s identity. The relationship between positive identity and awareness of discrimination matches with previous work on the subject (Uchida 2005), and we can interpret this as indicating that precisely because of a positive identity one more directly faces discrimination and therefore is more sensitive to it.

Table 4 shows correlation coefficients for identities parameters and experience of discrimination.

Table 4.Correlation Coefficient between Experience of Discrimination and Identity Variables (N=181)

|

Positive identity

|

Discomfort w

Discrimination |

Feelings of

Commonality |

|||

| I have experienced discrimination |

0.186

|

*

|

0.202

|

**

|

-0.010

|

| I have encountered or seen discrimination |

-0.065

|

|

0.137

|

|

-0.038

|

| No particular experience |

-0.111

|

|

-0.189

|

**

|

0.049

|

* The correlation coefficient is significant in 5% level.

*1 = Yes, 2 = No

“Discomfort with discrimination” shows a meaningful correlation to experience of discrimination. Those who answered “No particular experience” tend not to feel discomfort at the thought of discrimination, as common sense might indicate. Additionally, those with experience of discrimination tend to feel strong discomfort at the thought of discrimination.

However, there is a meaningful correlation between “I have experienced discrimination” and “Positive Identity.” We can see a tendency for those who have experienced discrimination to have a positive sense of identity. At this point we cannot provide an analysis of this result. In order to provide an answer to this question, qualitative research, such as a life-history interview, would most likely be necessary. That aside, just like discrimination awareness, the relationship between discrimination and evaluations of identity is more complicated than common sense might indicate.

2-4 Relationship to Awareness of Buraku Issues – Correlation of “Discomfort with discrimination” and anger with discrimination, of “Positive identity” and having a culture of which one can be proud

Table 5 shows the correlation coefficients for identity parameters and awareness of Buraku issues.

Table 5.Correlation Coefficient between Awareness of Buraku Issues and Identity Variables (N=196)

|

Positive identity

|

Discomfort with discrimination

|

Feelings of Commonality

|

|||||

| A | Burakumin should actively participate in the Buraku liberation movement. |

0.323

|

**

|

0.067

|

|

0.303

|

**

|

| B | Exchange between Burakumin and those who live around them is a good thing. |

0.430

|

**

|

0.197

|

**

|

0.168

|

**

|

| C | Burakumin have a culture one can be proud of. |

0.499

|

**

|

0.074

|

|

0.155

|

*

|

| D | Burakumin have strong feelings of mutual cooperation. |

0.229

|

**

|

0.019

|

|

0.239

|

**

|

| E | Burakumin highly value human rights. |

0.181

|

*

|

-0.093

|

|

0.163

|

*

|

| F | Famous Burakumin should make their identity clear. |

0.325

|

**

|

-0.260

|

**

|

0.211

|

**

|

| G | If you don’t mention Buraku discrimination, but instead ignore it, it will disappear naturally. |

-0.335

|

**

|

-0.153

|

*

|

-0.003

|

|

| H | The responsibility for Buraku discrimination also falls on Burakumin. |

-0.168

|

*

|

0.031

|

|

0.007

|

|

| I | Buraku discrimination will not disappear no matter how hard you work against it. |

-0.274

|

**

|

0.085

|

|

-0.013

|

|

| J | A lot of Burakumin fixate on words and make the problem of discrimination. |

-0.101

|

|

-0.014

|

|

-0.079

|

|

| K | I am angered by Buraku discrimination. |

0.148

|

*

|

0.270

|

**

|

0.158

|

*

|

| L | Laws regulating Buraku discrimination are necessary. |

0.083

|

|

0.216

|

**

|

0.220

|

**

|

| M | There is no need to focus on one’s Burakumin identity. |

-0.227

|

**

|

-0.221

|

**

|

-0.119

|

|

| N | Buraku discrimination is slowly disappearing. |

0.041

|

|

-0.281

|

**

|

0.120

|

|

| O | Burakumin are sensitive to various forms of discrimination. |

0.012

|

|

-0.031

|

|

0.227

|

**

|

| P | Special measures for Buraku neighborhoods are still necessary. |

0.262

|

**

|

0.138

|

|

0.201

|

**

|

* The correlation coefficient is significant in 5% level.

* 5 = Strongly Agree, 4 = Agree, 3 = Neither Agree nor Disagree, 2 = Disaree, 1 = Strongly Disagree

Regarding “Positive Identity,” there is an apparent tendency to have a positive evaluation of identity among those who answered positively to “C Burakumin have a culture one can be proud of,” “B Exchange between Burakumin and those who live around them is a good thing,” “F Famous Burakumin should make their identity clear,” “Burakumin should actively participate in the Buraku liberation movement,” “P Special measures for Buraku neighborhoods are still necessary,” and negatively to “G If you don’t mention Buraku discrimination, but instead ignore it, it will disappear naturally,” “I Buraku discrimination will not disappear no matter how hard you work against it,” “M There is no need to focus on one’s Buraku identity.”

Regarding “Discomfort with Discrimination,” a tendency to have strong discomfort with discrimination was apparent among those who answered positively to “K I am angered by Buraku discrimination,” “L Laws regulating Buraku discrimination are necessary,” and “B Exchange between Burakumin and those who live around them is a good thing,” and negatively to “N Buraku discrimination is slowly disappearing,” “F Famous Burakumin should make their identity clear,” and “M There is no need to focus on one’s Burakumin identity.”

Of note here is the response “M There is no need to focus on one’s Burakumin identity.” Regardless of whether you value your origin positively, regardless of whether you feel discomfort with discrimination, in order to make that evaluation, you must have, to some degree, an awareness of identity.

2-4 Relationship to Conversation about Buraku Issues

Table 6 shows the correlation coefficients for identity parameters and whether the respondent talks about Buraku issues with other people.

Conversation, independent of conversation partner, appears to have a positive effect on “Positive Identity.” Frequent conversation and a positive identity evaluation are linked.

On the other hand, “Discomfort with Discrimination” appears to be primarily correlated with conversations with “C Siblings,” “B Mother,” and “F Buraku friends.” We can see a tendency for people who indicated a high discomfort with discrimination to speak with these people. We cannot ascertain the contents of those conversations from the results of this survey; however, it is possible that discomfort with discrimination might be the subject of conversation.

Table 6. Correlation Coefficient with Conversations about Buraku Issues

|

Positive identity

|

Discomfort with discrimination

|

Feelings of Commonality

|

|||||

| A | Father(N=176) |

0.226

|

**

|

0.100

|

|

0.127

|

|

| B | Mother(N=189) |

0.256

|

**

|

0.155

|

*

|

0.081

|

|

| C | Sister or Brother(N=181) |

0.317

|

**

|

0.168

|

*

|

0.047

|

|

| D | Grandmother or Grandfather(N=145) |

0.194

|

*

|

-0.025

|

|

0.201

|

*

|

| E | Wife or Husband(N=53) |

0.400

|

**

|

0.046

|

|

0.197

|

|

| F | Buraku friend (N=183) |

0.371

|

**

|

0.151

|

*

|

0.197

|

**

|

| G | Non-Buraku friend (N=189) |

0.440

|

**

|

0.040

|

|

0.178

|

*

|

* The correlation coefficient is significant in 5% level.

* 4 = Often, 3 = Sometimes, 2 = Rarely, 1 = Never

2-5 Relationship to Image of the Liberation Movement

Table 7 shows the correlation coefficient between identity parameters and perception of the liberation movement.

As for “Positive Identity,” “J The movement has no relation to me” shows a particularly high correlation coefficient; we can see a tendency for those who do not think this to evaluate their identity positively. Additionally, people positively evaluate their identity who characterized the movement as “H Working toward aspirations,” “D Working for the benefit of residents of Buraku areas,” “B Showing strong solidarity,” “F Cool,” and negatively to “G Difficult to approach,” “E Too stiff and formal.” Closeness to the movement, or their image of the movement, is strongly tied to the positive identity of Burakumin youth.

As for “Discomfort with Discrimination,” we can see a tendency for those who characterized the movement as “G Difficult to approach,” “A Frightening,” “I Disregard youth” to display strong discomfort with discrimination. A poor characterization of the movement correlates with “Discomfort with Discrimination.”

Table 7. Correlation Coefficient between the Image of Buraku Liberation Movement Recognition of Discrimination and Identity Variables

|

Positive

identity |

Uneasiness

to discrimination |

Common

feelings |

|||||

| A | Frightening (N=193) |

-0.142

|

*

|

-0.242

|

**

|

0.034

|

|

| B | Having solidarity (N=195) |

0.243

|

**

|

-0.024

|

|

-0.283

|

**

|

| C | A lot of injustice (N=194) |

-0.060

|

|

-0.179

|

*

|

0.003

|

|

| D | Working for the benefit of residents of Buraku areas. (N=195) |

0.267

|

**

|

0.115

|

|

-0.132

|

|

| E | Too stiff and formal (N=194) |

-0.208

|

**

|

-0.098

|

|

0.209

|

**

|

| F | Cool N=193) |

0.244

|

**

|

-0.040

|

|

-0.044

|

|

| G | Difficult to approach (N=193) |

-0.232

|

**

|

-0.266

|

**

|

0.079

|

|

| H | Working toward aspirations (N=193) |

0.388

|

**

|

0.026

|

|

-0.271

|

**

|

| I | Disregard youth (N=193) |

0.027

|

|

-0.221

|

**

|

-0.103

|

|

| J | The movement has no relation to me (N=193) |

-0.500

|

**

|

0.134

|

|

-0.005

|

|

* The correlation coefficient is significant in 5% level.

* 5 = Strongly Agree, 4 = Agree, 3 = Neither Agree nor Disagree, 2 = Disaree, 1 = Strongly Disagree

2-6 Relationship to Sense of Community

This survey also inquires into the respondents’ sense of community in the neighborhood in which they live. If we only take those who live in Buraku neighborhoods, we can analyze the relationship between sense of community and the identity parameters.

Table 8 shows the correlation coefficients of the identity parameters and the sense of community index.[5] A meaningful correlation can be seen along “Positive Identity.” A strong sense of community correlates with a positive evaluation of identity.

Table 8. Correlation Coefficient Between the Community Index and Identity Variables (N=133)

|

Positive

identity |

Discomfort

with discrimination |

Feelings

of Commonality |

||||

| Community Index |

0.560

|

**

|

0.021

|

|

0.337

|

**

|

[1] There are many studies calling attention to the consciousness of Burakumin, for example Yamamoto (1959) and Wagatsuma Hiroshi (1964). These studies pay particular attention to the stresses placed upon the self-image (nowadays called identity) of Burakumin facing discrimination. However, identity research reappears in the 1990’s (for example Nishida 1992, Yagi 1994, Kuraishi 1996, Matsushita 2001, Matsushita 2002, Uchida 2005). The reason for this is that, with the entry into discussions around the Dowa Measures and at the urging of the movement, Buraku issues were problematized in two directions: “inferior environment” (actual discrimination) and “the consciousness of those who discriminate” (psychological discrimination). As this became systematized, the perspective of the consciousness of Burakumin dropped out of the picture. There was the concern that investigations into the consciousness of Buraku residents would prompt criticism of the consciousness of Buraku residents as a cause of discrimination.

[2] There were a variety of reasons why respondents considered themselves “Burakumin”: 64.4% said because they “live in a Buraku area,” 59.9% because they “were born in a Buraku area,” 48.0% because their “permanent registered address was in a Buraku area.” We can see in these answers a tendency to define “Burakumin” according to the geographical unit, “Buraku.” An additional 27.2% gave the reason as “because I think so.” Whatever criteria other people might be using (such as relationship to a Buraku area), over one quarter of those who thought themselves Burakumin do so simply because that is their identity.

[3] The results from this study do not show tendencies for all Burakumin youth residing in

[4] I allowed the following as possible responses: “5 strongly agree” “4 agree” “3 neither agree nor disagree” “2 disagree” and “2 strongly disagree.”

[5] The sense of community index is calculated from the sum of responses to questions about sense of community that measure one’s attachment to, participation and integration in, and evaluation of the community in which one lives. The following points were assigned: “Strongly agree” 5 points, “Agree” 4, “Strongly Disagree” 1.

| Back | Back Number | Home |