International Workshop and Symposium of Young Scholars Working on "Present Day Buraku Issues"

|

||||||

|

What is our real name? Movement and practice for environmental managementComparative case studies on an indigenous communityin Australian and on a Buraku community in

(original: Japanese) TOMONAGA Yugo / MORI Maya |

||||||

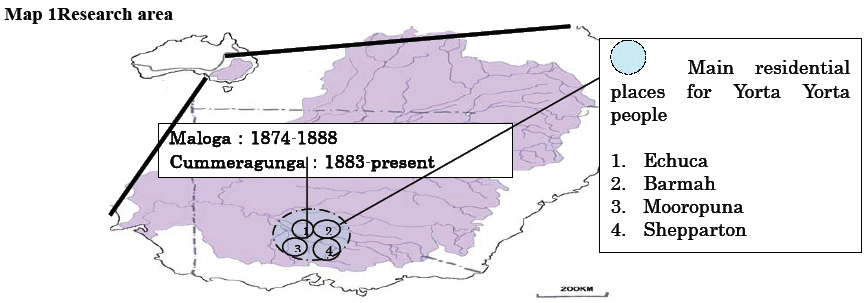

AbstractThe beginning of my study can trace back to 1998 when I joined the international Human Rights Exchange program with Australian indigenous people held at a Buraku community in Kagawa prefecture. I had big influence on my life and my thought to Buraku problem and it liberation movement through this program. Thought the middle and long term field work, I have gradually realized how I can compare and contrast between Buraku problems and Australian indigenous peoples problem and how we can share our knowledge and experiences for our practical movements such as the movement for the environmental management. In so doing, recently I am taking the comparative research between Yorta Yorta Aboriginal community at the south east Overview of Research AreaThe main areas of my study are the following towns and city located on around 250 km up to the north from the Melbourne city; Echuca town, Moama town, Barmah village and Cummeragunga Aboriginal community around Barmah forest, and Mooroopna town and Shepparton city along the Golbern River diverging from Murray River. Barmah forest is part of the largest River Red Gum wetland in the world with the second longest White

|

|

Fire management during spring and autumn month when there wasn’t fir danger. They never ever done it in the summer. You know all of the carbon was moisture then burn was really slow.. so total fire they never ever burn in the summer month because we have now drought for years so it gonna be, you know, we don’t have any rain we don want to be able to do it. because forest was dray. All under ground just exploded. you know One fire start up we never do it about burn, it is traditional burn. The way to destruct effective to the areas yah.[6] |

In the past time, flood season was end of the winter or beginning of spring until 1919, but this season was changed to the end of summer or beginning of autumn because the dams and reservoirs along the

Fishing in Leisure

From July to September 2007, every weekend I joined the river fishing with three Aboriginal males (2 males are not Burkanji descendants and 1 is Yorta Yorta) and inquired how to use river resources in their daily lives through Video taking. The elder Colin Walker addresses the following comments on how the relationship with the river is important part in Yorta Yorta individual daily lives;

|

In the Place where I grown up, Government came to house and check the table. There wasn’t any food on the table and thought kids didn’t have any food and some of them were removed from parents but it was totally wrong. Our table is not in the house but here (forest and river). They are big market for us.[7] |

Yorta Yorta female elder

|

I remember playing along the river when I was seven, seven years old. And always have my friend with me, my girl friend, my cosines and my little sister. And walk along the edge to the river. And get tins out of the water that was in land for couple of days. We tip up a little fish and tip up yabbies and slinps we put them on the bank to save them up and we followed to the mussels we were going thought the mud and they were lovely memories even for now when I think about what it is used to along the river because water was very clear. we had ween reed when we were just swimming around the river but we see light bottom at the river in the middle, very clear water and you don’t see that now.[8] |

Yorta Yorta male and a board member of Yorta Yorta Nation inc, Peter Ferguson explains;

|

When I was kid, I used to see down about 12 feet or 13 feet in the water 14 feet and you will see the fish swing about this big though, Yellow bally and Red fin. It was seen swing around. We used the jug what I said has a two hooks at the bottom what Im saying. But river was so clear in those days what I am saying. I used to put the fuck over the next to the fish and we jugged fish what I am saying. Yah, it would be long, what I am saying before moved the further we catch a potato sec full of a red fin or yellow ballys and we take them back up home Mooropoona to share all with uncles and unties cousins that sort staff.[9] |

Comparing with above Yorta Yorta individual memorial accounts, the number of native fish decrease at present and the quality of the river also has been worse since 1960s.

|

Forest it is one of the biggest forest in Oh our lakes we got Barmah lake and Moira lake and when you look at the map. It like a river our elders before it was used to say it was living things because lacks on the each sids looks like a kidney and river run down through the lacks in the middle of the lacks were the spine. yha. Then if you look at properly you will see it looks like human body. And little creek through running of forest looks like vein. Veins on the water getting on the running in keep. . . purify the lakes just our vein, our body , and our blood purify our kidneys.[10] |

The environmental management for Yorta Yorta means that they take care of the river and the forest succeeded by their ancestors, which provide ‘the most important thing for living’.

Meaning of the Movements from Yorta Yorta Accounts

As for the meaning of the Land Rights movements, according to the interview from Yorta Yorta individuals, 20s, 30s and 60s aware the difficulty in making decision of their Country but most of all recognize Barmah and Cummeragunga as their country. All interviews had or have experiences to join land rights movements. As for the role of elders, except one negative opinion from 20s, all interviewees evaluate the significant role of elders in that they can learn lots from Elders in the present. However more than 40 years old interviewees stress the point that elders lost their trust from young generations. As for the oral tradition from present generation to the next generation, all interviewees emphasize a strong self-esteem as Aboriginal and skills on hunting, fishing and gathering as well as ritual things.

The meaning of land for the Yorta Yorta through these actions appear in the following account from the Yorta Yorta male Neville Atkinson.

|

(The land right movement is). . . Something we need to give to our people, particularly older ones so they can say their life is going something you know. . . Keep Yorta Yorta people encourage younger ones. Just say if we keep, keep do then doing and stand our ground nature identity (that) it is here, it maintains it.[11] |

Conclusion

This presentation has tried to clarify the relationship between Indigenous people and local people concerning the Yorta Yorta land rights movements. Consequently, it revealed that the present movements and practices of the land and river management still rely on the conflict situation between Yorta Yorta and other stakeholders, which has been razed since the colonial time. Furthermore, it can be said that the meaning of the land right movement for Yorta Yorta is ‘the movement for environmental management’ through the following two perceptions; first is ‘the reward for our elders effort and the strong self-esteem for the next generation.’ and another is ‘nourishment for life’ inherited from ancestors.

Recent Yorta Yorta land and water movement has been taking a new sift from the conventional binary and homogenize structure, which consists of Indigenous people, local people and governments to the multiple structures, which consist of the local and international NGOs and the urban intellectuals.

The different opinions on the VEAC proposal have deeply related with the colonization but what is an interesting in this situation is the part to play of the local and international NGOS and urban intellectuals. Due to their intervention into the Yorta Yorta movement for environmental management, what local people is opposing is not to the indigenous people who identifies as identifiable community under the Native Title act but to Yorta Yorta who identifies as indigenous nation, which has the rights to control their natural resources on the ally with local and international NGOs and urban intellectuals. The Yorta Yorta rand rights movement through the Indigenous nations and the co-operative agreement dose not require who indigenous people is but places in the contact zone where both indigenous people and other stakeholders can be adaptable in the new unsymmetrical power structure when they contact each other.

MORI Maya

My field site, the A area, is a non-urban Buraku community outside of

I have lived life feeling bodily this multiple historicity. At university I studied sociology where I developed an interest in the current situation of issues of Buraku discrimination, the limits of standardized research on representations of Burakumin and their identity, as well as Buraku communities. Within the realm of Japanese sociology, issues of Buraku discrimination became the subject of academic inquiry in the 1980s.

In 1980, Shikimoto Gotaro (then the vice-chairman of the Joint Association of the Kanagawa Prefecture Buraku Liberation League), participant in the Japanese Sociology Association, left behind these words: “I witness here a discipline disconnected from the aspiration of ending Buraku discrimination. This is argument for argument’s sake. The perspective of human liberation is exceedingly far, far, far away from the world of the academy” (quoted in Fukuoka Yasunori, 1980). These words offer an important suggestion for those advancing research in the context of Japanese Buraku.

This is to say, the “practice” of academia is distant from the practice of those people who hope to eliminate Buraku discrimination, who believe in human liberation. This is not a problem of being objective or subjective; rather, it is an issue of the perspective with which researchers approach the practices that comprise the existence of living people.

As I continued to graduate school, I began to realize, cued in by the history of A where I lived and the life histories of its residents, the importance of recording for future generations the wisdom and knowledge born of human beings that I saw in the figure of the A area as told by the people passing through the area.

In this symposium I take as my example concrete practices and lived Buraku history in order to incorporate the “knowledge” of people’s everyday life into the realm of academia or theory, and I would like to emphasize the importance of doing such a thing when discussing “present day Buraku issues.” I also am participating as a panelist in this symposium as a younger person responsible for carrying the Buraku liberation movement into the next generation, and in order to increase the possibility that minorities themselves can share concrete practices from their lives with each other and with researchers.

Introduction

The

A’s Buraku liberation movement has an indescribably long history of managing the rivers, forests, and land of the area, and the struggles over education, run by parents and children, was started in the A liberation movement. In this paper, I examine the “present day Buraku situation” by taking up examples from the management of 1 rivers, 2 water works, and 3 forests.

1. The River of B

In the Souka Record of Kamayama Hanshi of 1844 (the 15th year of Tempo), there is a record from an interview in Anainu Village, which neighbors the A area: “To the north-east of this village, there is a small stream, a river of heaven, that has been well known for ages among the people of the Anainu Village.” What is currently called the “

Following the modern period, there were repeated floods of the “

Almost twenty years later in 1989, one paragraph of the introduction entitled “Everyone’s Request” of the publication “A Glimmering Life” spends time reflecting on the joy of the village people when the administration started to reconstruct the river and repeats the statement of the then organizer of the A Buraku Liberation movement, Mori Emiko, reflecting on what the people of A had lost:

The widening of roads and building and large magnificent buildings took what little land we had, and broke apart the life-line of the villages, our sense of community. Our narrow though rich stretches of soil, glistening darkly, were filled with pesticides and bleached a dry unhealthy red; the fish and fireflies no longer gather; and our once playful river has, for the sake of “development,” been overlaid with cold concrete. With this our spirits too have been battened down. We are not poor because we lack things, we are poor because we have lost our spirits.

There is no doubt that the reconstruction of the river, while it was, in form, what the residents of the area had requested, was not open to the residents’ participation in detailed planning, and did not yield the result they had imagined. This social situation, and this woman’s words, remind us of Franz Fanon’s theory of the bridge:

If the building of the bridge does not enrich the awareness of those who work on it, then the bridge ought not to be built and the citizens can go on swimming across the river or going by boat. The bridge should not be ‘parachuted down’ from above; it should not be imposed by a dues-ex-machine upon the social scene; on the contrary it should come from the muscles and the brains of the citizens. . . so that the responsibility for [the bridge can be] assumed by the citizen. In this way, and in this way only, everything is possible. (Fanon: 1961)

2. The A Water Supply: Honoring water for its warmth – a story of the water of life

There is a small-scale water supply in A that is said to be the origin point of the liberation league of Kameoka city. In 1955 the A district, then approximately 75 households, had 4 wells within its boundaries. However, the quality of the water was troublesome, and people lived in fear of communicable diseases. One of A’s elders, Maeda Yuzuru recalls, “The call for water facilities in A sprang from the kitchen rumors of women and learned from historical uprisings around rice. . . The cry for liberation from a desperate life, from a life without safe drinking water, initially the cry of a few, became the cry of the entire community, and developed into a community movement.”

In addition, an elementary school teacher from that time, Hirotomi Yasumi, added the following:

Our daily lessons are completely different from how they used to be. The joy of being able to wash your entire body in water like a ball erupting forth has given hope to our students’ lives. The light in their eyes, the bounce in their voice all testify to this change. It really is the water of life. These children, who have grown up with the fight for water, have had their paths lightened by this change. With the organization of the liberation movement, the children were right in the thick of pumping the water, pulling up the hoses themselves. Before that, they had helped their parents pump water from the old wells and had the first hand experience of being distant from the blessings of nature; they and their parents struggled together. With that experience, the struggles of the parents’ of the community were, like it says on the monument to the water system, “born out of the heart-breaking gift of labor, from the combination of blood and sweat and tears” and as expressed in the sentiment, “To future generations do we express – thanks for the water of life and the effort of our forefathers,” do we give thanks for the nurturing force of water in fulfilling our community’s ardent belief that “all people should be able to live happily” and that “with the effort of everyone, all things are possible.” These improvements will help us continue strengthening our community.

The resident’s struggle for water began with the demand simply for secure and safe daily drinking water, and in 1959 resulted in the water supply subsidy system. In 1960 the A water system was inaugurated. For the half century up until March of 2005 when the major water supply system was introduced, this water supply supported the lives of the people of A.

A’s “struggle for water was not simply for water; it, just like the building of the communal well in the Taisho period, involved all the members of the community coming together in the main hall of the temple, and discussing the issue for long hours day and night.” The resolution of A’s water issues was due to a large movement aimed at “protecting human life” – it is remembered now as “a bitter struggle on the part of women and children to protect, on rainy days as on frozen days, the life of the family in the struggle for water.” It is the “story of the water of life.”

3. The Struggle for the A Liberation Forest

In 1871, at the time that Meiji abolished clans and established prefectures, the allotments distributed for mining and the formation of grassland in the A area were unfair and resulted in the struggle for the A liberation forest demanding a more fair re-distribution. In June of 1974, with the decision of the Kameoka city council, A received control over the management of the liberation forest. The same year they started the A liberation forest union. The union bylaws included the responsibility and authority over the A liberation forest.

The primary objective of the liberation forest was to conduct proper management and care, increase the welfare and living standards of the union members, and increase awareness of the possibilities of liberation. Furthermore, the property rights include communal ownership by the residents of A, who would participate actively in the mountain and forest liberation struggle and correctly understand the objectives and requests thereof. The conditions of ownership included the intention of permanent residence in A, at least 2 years of humble participation in the Buraku liberation movement, and regular payment of dues as decided by general assembly.

Now, in 2008, though there have been slight amendments, A

Let us stop selling away the hearts of villagers for t he purpose of making people inhumane. The horror of discrimination is manifest not only in the figure of those who kill themselves rather than face discrimination. It is also something that without the slightest resistance cleaves to one's body in daily activities, and lives in perspectives, mindsets, and values that live only in that world. There are daily activities, and lives in perspectives, mindsets, and values that live only in that world. There are more and more people then who thing nothing of their district, nothing of jobs, education, or each other, who have their hopes for life stolen from them. The inheritance we receive from our elders, who have lived this far across a great accumulation of hardship, with this becomes smaller.

So far, I have traced the history and the practices of the A area. I have introduced the history of how a voice rose up from the lives of women to become the voice of the community and transform into a group movement, and how children who were raised in the struggle for water inherited the belief that anything is possible if you are willing to work for it. These children, who learned from the accumulated hardships of their elders, have grown up to be the leaders of the Buraku liberation movement in the 1980s, and they have transformed the definition of poverty from a simple economic and material index to a belief that “people are not poor because they lack things, they are poor because the have lost their spirits.” In 1987, as the reconstruction of the

The practices of people in Buraku communities are born of the quotidian lives of living people who come from specific land. It has been pointed out that in recent years, the development of a sustainable Buraku liberation movement is tied to increased awareness of environmental issues. However, the history and the composition of the Buraku liberation movement are different according to each Buraku community. The fact that a Buraku liberation movement such as A’s, born of a deep respect for life engraved in the hearts and minds of its people through the medium of water, can carry on its practice of environmental management even today, emphasizes the fact that other Buraku communities do not have the means to carry out sustainable practices. Moreover, it cannot ever be forgotten that solidarity of urban Buraku communities and the organizations, led by Buraku people, that develop the liberation movement have had their land taken from them without their accord, and have seen their land transform from fertile to barren soil.

An Ending to Begin

When we discuss “Changes in Buraku Identity,” the first things to be listed out are the flow of people in and out of Buraku communities, intermarriage, and changes due to increasing global interdependencies, and the decrease in the importance of Buraku communities is frequently mentioned. However, living people live lives of change, in step with social changes that are not limited to Buraku communities alone. The environmental management and practices of the Buraku liberation movement of the A area instead use those changes as a lever; the people who live in that Buraku community and the people who pass through it have been raised together on a foundation of deepening thoughts about the area’s environment.

I hope that from this point on, the approach of academic research to “Buraku Identity” will recognize the constraints of a one-sided image of the Buraku liberation movement, Burakumin, and Buraku communities, and begin a new process of subject formation. Also, I ask that, in order to ensure the autonomous rights of the people who comprise these communities, and to ensure their empowerment process, these people take back their real name, and establish a place for their daily practices as the basis for a new theory of liberation, in order to continue and pass on their activities.

Works Cited

[1] Since 2005, primary industry around the research area has been on the decline due to the long term drought.

[2] In Native Title 1993, there are three controversial points; 1.existence of an identifiable community, 2.traditional tie and possession with land in terms of traditional law and custom, 3. succession of tie and possession with land.

[3] Since May 2007, Darnya cultural center has been closed due to the white Ants.

[4] The State Government of Victoria 2004 Co-operative Management Agreement between Yorta Yorta Nation Aboriginal Corporation and The State of

[5] All belong to Yorta Yorta Nation inc.

[6] Walker, C. Interview with Author, his place at Cummeragunga, March 24 2008.

[7] Walker, C. Interview with Author, his place at Cummeragunga, August 23 2007.

[8] Macissen, F. Interview with Author , Yarapuna Lodge at Barmah , March 23 2008.

[9]

[10] Walker, C. Interview with Author, his place at Cummeragunga, March 24 2008.

[11] Atkinson, N. Interview with Author, his office at Shepparton, September 14 2007.

|Back|Home|